Finally, a critical book in Service Design that comes back to the materiality of services. For too long we fetishised methods and focused on the how not the what of services.

I have been vocal in the past on the challenge of the discipline focusing on how to design services with a lack of quality texts in what good looks like. Whilst no one person can claim to deliver the absolute closing word on what makes a good service, Lou Downe has given it a shot and had the courage to put it into print. And thank goodness for that courage.

The beauty is in the simplicity of Good Services. The language is clear, it’s simple and it’s really easy to get your head around, it doesn’t try to show off the author’s knowledge by trying to outsmart the reader. The 15 principles that came from an earlier 2018 blog post have been embellished with quirky and thoughtful stories that bring the principles to life and it really gets to the heart of the things you should consider when designing or running a service, at any level.

This is THE text of the moment on Service Design. I think this will be a critical text in the history of Service Design discipline alongside This is Service Design Thinking and doing.

Why? Because it can be read by anyone who has a hand in running or designing a service. It will be helpful in an innumerable amount of ways. Here are some I came up with;

Interviews for Service Design Roles

To date I’ve seen lots of designers and industry folks picking up this book and that’s great news for a couple of reasons.

Over the last decade I’ve conducted 100s of interviews and I’ve found myself often in a position being schooled in design methods — being led through tools and explained outputs of a process as opposed to outcomes of a service design.

I always tend to start with show me or tell me something you’ve been part of designing. Why? Because I want to get to the guts of how people think, that they understand the materials of what makes a service and have them articulate their role in moving beyond conceptual ideas into the graft of making a service or product come to life (or at least tried to) in some way. The challenge I’ve perceived has always been in people feeling they need to articulate service design methods they’ve learned rather than outcomes they’ve delivered. I really don’t mind what people talk about — whether they managed a hotel, helped construct a policy or prototyped a payment system. I want to see that understanding of the materiality of a service and the components that shape it (e.g policy, finance model, data, business model etc.), and that they can look up, down, left and right from the thing they are focusing on and balance this with striving to make it come together for the people who use and deliver it.

Whether people failed or succeeded, played a large or small part, its important they can convey how to deconstruct a service and use evidence to improve or reimagine it in some way.

And (spoiler alert) that’s the ending of the book. The most important thing is that people see services in the first place and that they are tangible things that can and should be designed.

In a future interview experience I’d want people to come through the door and tell me how they ‘made a service that sets the expectation a user has of it’ or made it ‘easy to find’. We can use the principles in this book as a way to delve inside how people see services in interviews.

Accrediting service design

If we’re going to have anything around accrediting service design delivery, then we should focus on the design of good services and the experience and evidence of doing so, rather than the current model(s) which ask to evidence the skills to run a service design process, which is why I’m currently dubious about current accreditation models I’ve seen. I agree with Mike Monteiro who makes a great case for some form of licensed practice in design but when our current accreditation models focus on the delivery of service design process towards implementation and knowledge of key literature it becomes an abstract methodology and discipline we hold utopian dreams of, like it’s a step by step, method by method process. This distraction takes us away from what we’re actually striving for — which is a good service design.

The principles could be a way of re-starting the accreditation conversation and laying a solid foundation for showcasing ability to design a good service. If you are going to be approved to deliver something, you should at the very least be able to articulate how you have designed and delivered a service to meet one of these. Our dialogue in the industry needs to go beyond the competency in service design method delivery as a marker of a ‘service design professional’, to one based on the experience involved in genuinely striving and designing good services. And that my friends, opens the discipline up beyond some kind of ‘magic’ or art school discipline into one where we can prove our experience through what we were involved in designing and delivering.

Going beyond designers and starting conversations

Service design is a team sport and the user experience is everyone’s business. Whether you work in a design titled role or not, you will be part of making micro decisions that affect the macro user experience on a daily basis.

This book needs to go beyond designers and our own industry, we (the design community) should know this stuff inside out. We need to hand it to clients, frontline staff, managers, executive teams to start discussions at various levels of service operation on how to align company strategy, organisational design and service delivery, with an ultimate impact on the end user experience.

What most people don’t realise in the consultant design bubble is that the innocent method of ‘ask why’ and ‘why doesn’t this work’ consistently can often be perceived as an attack on someone’s role and their decisions. That’s really hard if you have to be in there day in, day out. Our questions can sometimes come from nowhere.

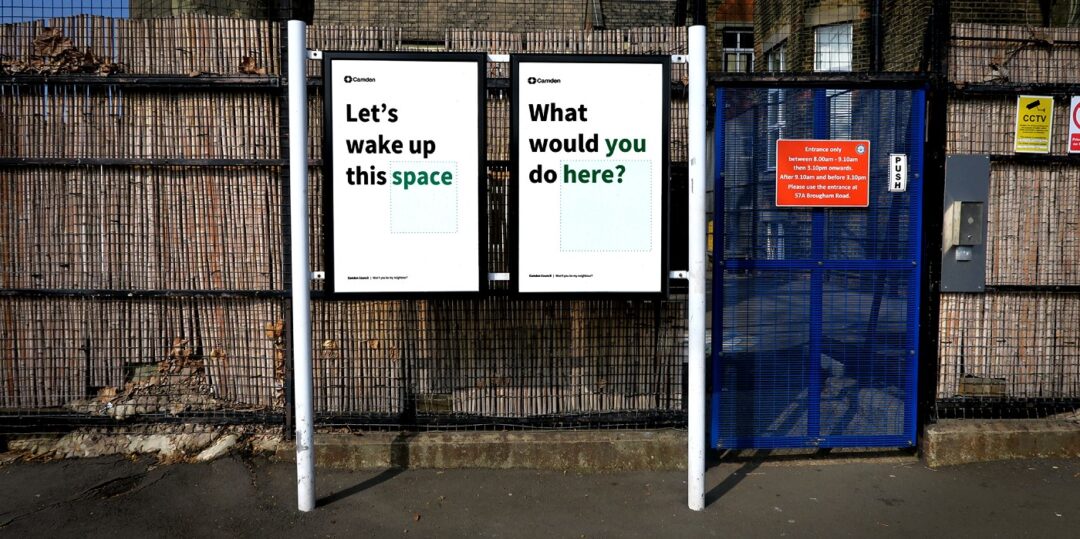

What the book and the principles provide us is a framework in which to hold conversations about the user experience and a shared investigation amongst colleagues, ultimately reducing the often perceived criticism people feel when they are asked directly about the thing they deliver. Instead of asking someone directly if something they are delivering is failing, we could bring them into the conversation collectively with other people involved in delivery to ask collective questions based on the principles like ‘does this service ensure it has no ends for users’? Or ‘is it is accessible to everyone who needs to use it equally’?

When the 15 principles first came out, we used it at Snook in some of our training workshops that bring together different members of staff involved in the delivery a service from multiple pockets of the organisation to investigate a service. We used the principles to review the service based on a ‘we totally meet this principle’ to ‘absolutely not’. This was a very simplistic framing and there’s definitely more space for a more mature weighting on how you answer this. Ultimately it didn’t really matter, it worked really well with our clients to start a conversation about the materiality of a service, take away any individual fear and allowed us to constructively critique the service experience as a starting point.

Furthermore from here, I’d love to incorporate the principles into researching the user experience so we go wider than a standard heuristic evaluation or frameworks like Net Promoter Score (which are so often used as a marker of customer satisfaction) and don’t pick up on the overall experience someone has in a service. The principles could help us to encourage a much wider research plan and re-design of the full end-to-end service across all channels of delivery.

That is only a few ways in which we can start to use the principles.

This is a critical text in Service Design. If you have anything to do with service design or delivery, go read it. When you’re done, give it to someone else.

This is the first time I’ve seen someone communicate what good looks like and capture attention from across the discipline in a long time, simplifying what has often be explained in complex terms that have only seen the light of an academic conference.

There’s not one point in it I disagree with.

Could there be more for different contexts? Probably. Is everything in the world a service that we can apply these principles to? No, don’t be daft, the world is far more complex than services alone.

But Good Services keeps it simple and easy enough to remember.

We don’t need to be strict about the way you use them. The principles are here for a conversation, to ask ourselves key questions and remember that services can and should be designed.

My hope is that once we’re done taking this book in, we can move the conversation on. When we expect everyone to be involved in designing services (because we all have a stake in it), and we build basic design literacy through training – it’s not enough. We need to know what good looks like. Good services finally give us a simple framework to have a conversation about good and apply it into our designs.

And this is 220 glorious pages of good.

Full disclosure, I am married to Lou! But, I do think this book is great. And I wasn’t allowed to read it before it came out, so this is a genuine review!

If you want to purchase it now, you can from the publishers BIS or wait for cheaper P+P on Amazon, which ships in February.