Service design has had a meteoric rise over the past decade. The discipline has helped us to make services more accessible, usable and inclusive. It has, in turn, made services more efficient and less costly to deliver.

This success has been widely recognised, and service design is increasingly being accepted as a key way to improve user experience, especially in the context of digital design.

It should come as no surprise that co-design techniques have underpinned community and neighbourhood development for decades — Stanley King started work on this in the 1970s — but it’s time for these techniques to be revamped, particularly with regard to digital. We need to find ways to adapt and influence service design practices to better serve communities.

Over the past 10 years, service design advocates — the team at Snook amongst many others — have made user needs a fundamental part of the design of services. All sorts of organisations have now adopted ways of working that put humans at their heart — and we know that helps to make the world a better place. Good conscious design can help build a world that is accessible for many more people, that creates inclusiveness for all and that recognises that the best solutions are those based on appreciating individuality.

But this approach must not be limited to the ways in which individual citizens relate to services and to one another. We can extend this approach to embrace whole communities, providing services in a more relational and less transactional way.

In the mid-20th century, a new form of public services arose, which moved provision from the charitable foundations of the 19th century to a universal model. Charitable hospitals and schools were replaced by public institutions. This was an enormous step forward, but it retained the structure of charitable services.

These services focused on a ‘deficit’ model, which saw users of services as passive recipients with needs and problems to solve — pupils and patients were subject to interventions.

The ‘deficit’ model cured smallpox, sent many other infectious diseases into retreat, and improved health, education and housing for almost everyone, and it continues to do so. In 2009 the Scottish Government acted on evidence identifying the human papillomavirus (HPV) as a cause of cervical cancer. It created a national vaccination programme for HPV which, over 10 years, reduced the number of pre-cancerous cells discovered during screening by 90%.

While we are very adept at deploying this type of ‘delivery state’ solution, we need to adopt a more relational approach to complement it. What we need is an ‘asset-based’ model — a model that starts from the humanity and strengths of the person. By making people partners in services, we can make those services more human. This is the right thing to do and, crucially, makes services more effective. Our challenge is to find ways to do this on a community-wide scale.

The ‘deficit’ model has crept into service design — we focus on problems and seek to solve them — and we must be careful that it does not overshadow our recent learnings.This is a useful way to approach problems in user-experience design. It helps us to design better interactions for users. But when we take this approach to a systematic level it discourages the individual and the community from counting on their own strengths and capabilities.

We now need to take our learning from both the delivery state of the mid-20th century and the human-centred design approach we have used to transform services in recent years, and adopt it for communities. We call this the ‘relational approach’. It is based on the principle that humans are cooperative and collaborative and that if we can create the structures that facilitate this behaviour then we can create a better society.

Just as the delivery state cured smallpox, so the relational state is needed to address contemporary problems — such as cancer and obesity — which have causes and cures that are simultaneously unique to the individual, and rooted in the relationships that individuals have with their networks and the places they live.

At Snook we have been doing work using neighbourhoods as the unit of change, experimenting with relational approaches, and focusing on strength-based service models.

We’ve been working in West Sussex to redesign the system for dealing with homelessness. By working with people with lived experience of homelessness, commissioners, providers and senior executives, we’ve been taking a step back to ask, ‘What does this system need in order to give people the opportunity to live the life they want to lead?’.

Instead of seeing the individual as a problem to solve with a long list of needs focusing on mental health, addiction, and self-harm, we’re focusing on, as one provider said, ‘what they want’. We’re working with West Sussex to look at the mechanism for commissioning more relational services, a system that builds support around a human being. Think of a coach who helps them be what they want to be and works with them on this journey. Not 6 or 7 ‘experts’; not endless letters and forms to fill in; or repeating their story to multiple professionals. One person, one relationship, and one supportive journey that’s open to moving forward or pausing at any time.

While asset-based relational approaches may appear jargon-heavy, the principles are simple: services should be developed on the basis that ‘nothing for us or about us should be done without us’; meaning communities should be at the heart of the design and delivery of services. Moving from needs to wants, and learning how we create the structures that enable institutions to design across systems, is a radical mindset shift for the service design community.

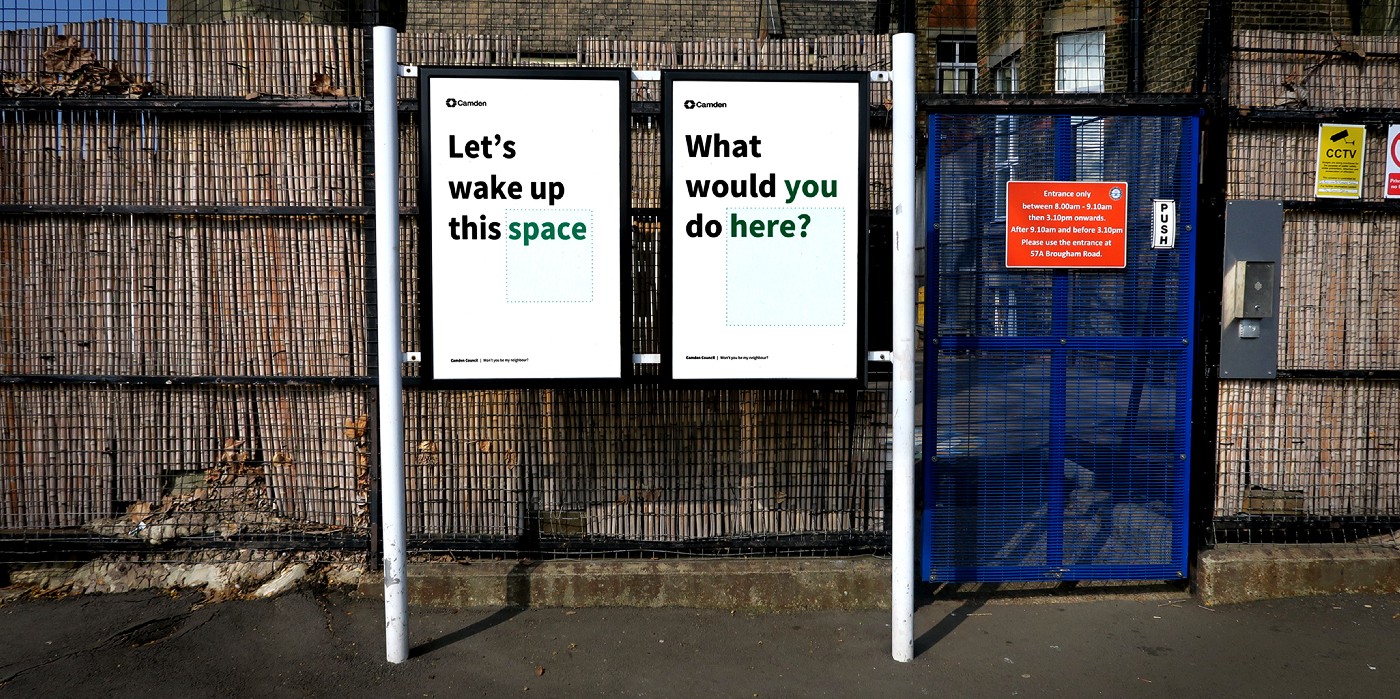

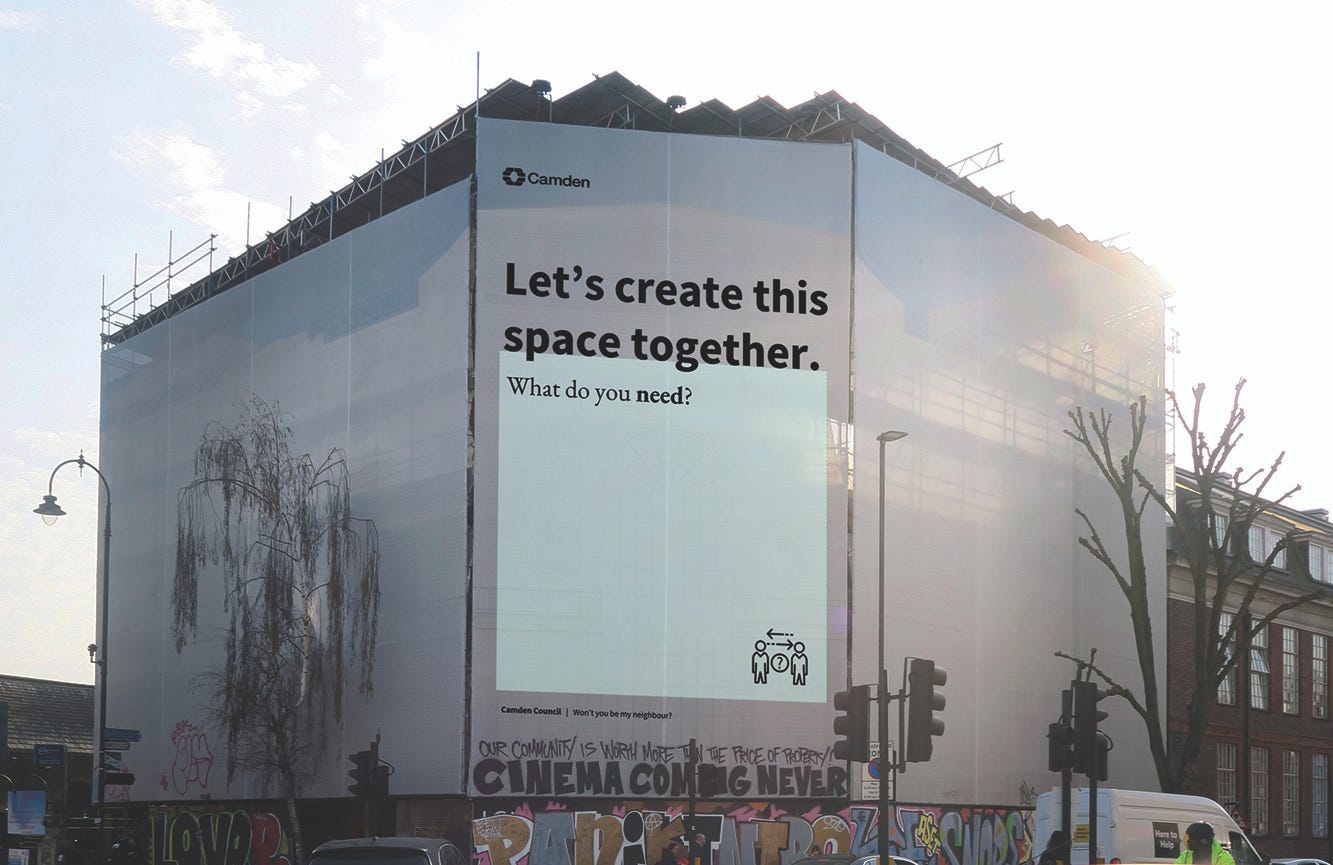

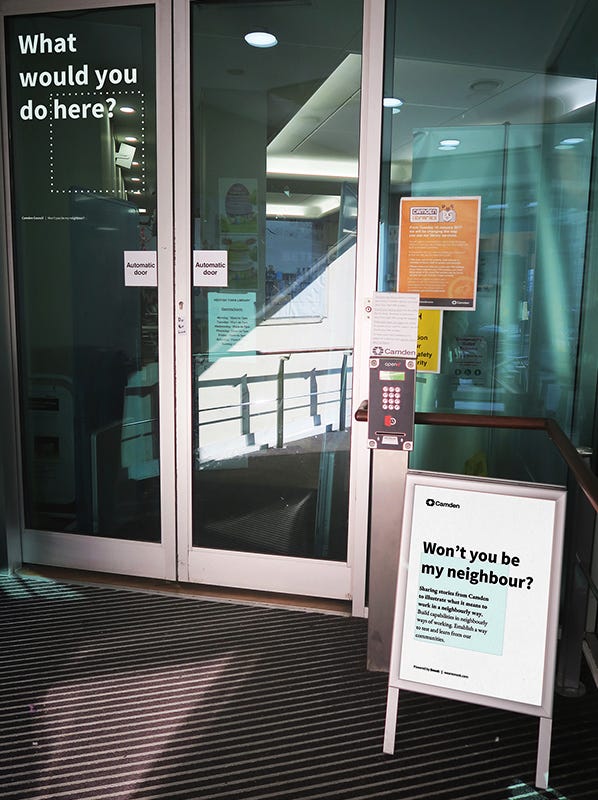

Snook are supporting service transformations in the London Borough of Camden where the council is facing complex challenges. Our work brings relational, asset-based approaches to this reconfiguration of its services.

We’ve been working with the Sport & Physical Activities teams in Camden to help them understand the barriers to physical activity. The opportunity to apply relational approaches came through the re-contracting of the leisure centres in the borough. Instead of looking at ‘the needs’ of the community in relation to leisure centre services, we mapped the assets and identified what the system of physical activity is across the borough, asking ourselves, ‘how we can strengthen it?’ By stimulating what is already working, we encourage a system-wide approach to increasing physical activity in the borough that has designed itself to be unique to the individual needs of the diverse community it serves.

To enable this, we looked at the re-tendering process of the borough-wide leisure centres contract, creating a strategy to join up and stimulate local activity across the borough that asked potential providers to propose how they would deliver services and support the system of physical activity already existing in the community.

Our strategy has included considering how the physical environment could be tailored to facilitate activity — both in leisure centres and borough-wide — by finding new ways to use libraries as public spaces, and neighbourhood hubs to co-design and deliver community initiatives. It’s reconstituting the partnership between the council and citizens, from delivery state to co-production.

Towards new models of community relationality and services

The NHS was based on the Tredegar Medical Aid Society, a mutual aid society formed by miners in Wales to provide healthcare to themselves and their family. While this was based on a private insurance model, it created a culture of care that became a foundational value for the NHS, the solution emerged from the community and was controlled by the community. We need to pioneer new models that address the challenges of today’s society in the same way.

We believe that an important part of developing these new models will involve using service design approaches to create new ways of working. By mapping community needs we can begin to build platforms that allow people to share. Tool libraries and lift sharing schemes are some that are leading in this space, so what are the service models of the 21st century that will engender relationality and support the strengths of community platforms?

Collaborative design of the physical infrastructure, bringing generations together, will create living streets, helping people to be more active. There are countless opportunities within communities to, for instance, help people manage health conditions, or use the power of the crowd to understand air pollution and possible solutions to name but two. We need to ensure that being relational is rewarded. Too often it is a cost.

For Service Designers, this requires a radical shift in mindset from problems and needs to strengths and assets. It requires a new familiarisation with the service models and materials of relationality. The role of the designer won’t be eradicated; there’s a role still for experts who can shape the materials of data, platforms and systems and how these are constructed for the production of scaled services and community platforms.

Service design brought method to the delivery of services; it has created a world where people are at the heart of services. Now is the time to take that approach to our communities — both of place and interest. Just as our world was transformed by the eradication of infectious diseases, creating a relational state will allow us to address the grand challenges of this era.

This article is co-written by Sarah Drummond, CEO at Snook and Peter McColl, Head of futures and policy at Snook

Featured by the lovely folks at The Service Gazette