I’ve been responding to requests for bids from clients in the form of ITTs, RFQs, Briefs, Proposal requests — for over 10 years, across the public, private and third sector for my company Snook.

Even after all this time, I’m still surprised at how some of the small things that our clients do at this stage often make it very hard for them to get good results from the work they commission later on.

Procuring design can be a tricky business if you’ve never done it before, or you’re having to explain what it is and what you need via a procurement department.

It’s even more difficult when you are protected by rules that ensure you don’t discuss the job in hand with potential suppliers .

The market is increasing in size with more people eager to commission Service Design, and even more people trying to sell it.

With an increase in the popularity of Service Design (and ‘design thinking’), I’ve seen a growing trend towards clients asking for service design without necessary knowing what it is or how to integrate it with the other outcomes they want to achieve from a given scope of work. ‘Service Design’ has become a catch all for any kind of change, making it increasingly hard to buy as a service from an agency or supplier.

I want the people I work with to get the best possible results — so I’ve written a 16 (awkward) part guide on how to buy service design.

It’s not exhaustive, but rather a list of some helpful tips that might help you if you’re involved in commissioning or selling service design.

I find that these elements help both sides reach a quicker understanding of what’s needed.

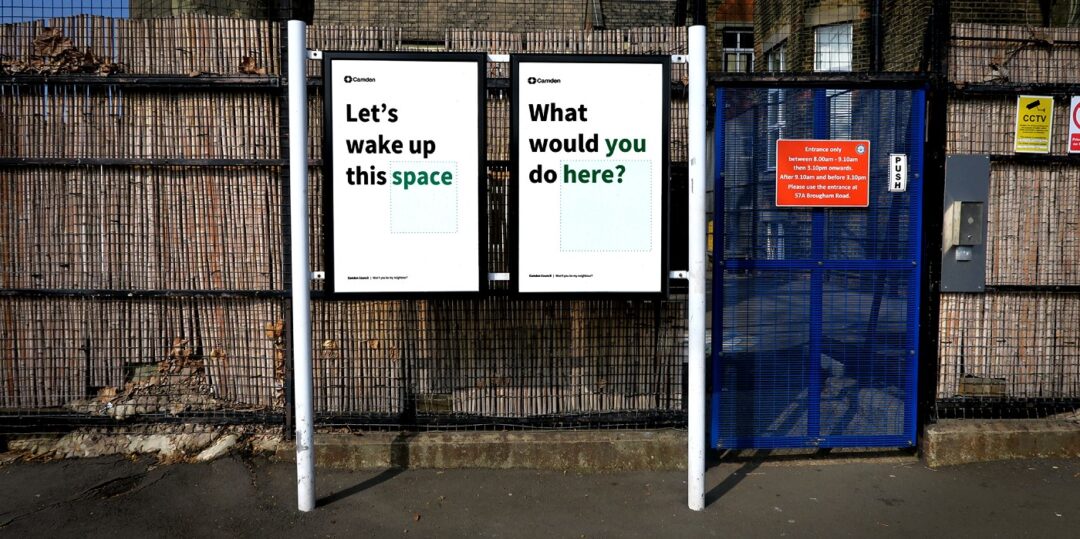

1. Be clear about what problem you’re trying to solve

Start with a clear intent, and don’t use ‘Service Design’ as a catch all for all ‘creative’ or ‘innovation’ projects.

Normally it’s good to start with a problem to solve that you have either evidence for but if you don’t know what the problem is, describe the issue you need to explore.

Here are a list of potential starting sentences and project types that I use to describe the different asks that come to us. They help us to define what kind of team we might put on our projects and how we might help answer the ask.

Problem defining and service design: We’re looking to understand why a service we run doesn’t work and how we can improve it

Digital channel shift: We’re looking to exploit digital as a way to scale our service offer

Proposition development: We’re looking to develop a clear product proposition and service to deliver it

Service Design: We need to design a service for the future

Product innovation: We need to think about the wider user experience of a product we deliver

Detail design: We’re looking to design the end-to-end service in detail at a delivery level

Technology driven innovation: We’re looking to understand an opportunity with a new technology we’ve discovered

Capability building: We’re looking to build our capacity to design services and re-align our internal structure to facilitate this

System and problem shaping: We’ve got a big challenge around X and we need to find a way forward to tackle it

User research: We need to better understand if we need to build a service or how we can better meet the needs of a user group.

We need to transform our organisation to centre around our customer needs and set a vision for where we are going.

This isn’t exhaustive but it might help you think about the intent of your project over the process of Service Design.

2. Set a budget or investment bracket

People often ask me ‘how much does service design cost’ and the honest answer is — it depends entirely on what you want to achieve.

Not setting a budget leaves an agency in a difficult position to consider how deep you want to go, for what length of time, if you can add on other deliverables that will enhance the final design. It’s like shooting in the dark.

Without a budget we can’t understand your level of investment and are left without understanding if you have the funds for a Ferrari or Fiat Panda. This isn’t about selling you dead time — we make our client’s budgets work to maximise the value they get for the time they can afford.

Budget can mean the difference in numbers of research participants to how long we spend on shipping the design. A budget range from x to x is fine but at least give the responders somewhere to aim for.

Without this, you end up with either unrealistic budgets where agencies try to over promise or proposals that shoot way beyond what you were looking for or able to invest in.

3. Focus on outcomes not outputs

Ensure your brief or tender focuses on outcomes not outputs. When you ask for a report at the end, you’re laying the focus on the delivery of the thing, not on the knowledge you need to make the right decision to deliver or design a service.

Try dropping reports out from your deliverables and instead focus on a KPI or outcome along the lines of ‘We need to have a concrete understanding of the existing user experience so we can take the right decisions on what we need to change’

Be flexible for that output to change, just ensure you map what you need to know at each stage of the project and work collaboratively with your partner to identify the right format as the project begins to close.

Treat the project as a learning experience and consider how your organisation can join the journey of knowledge development. I’m not adverse to writing reports, but if the focus is on an agency to write a report to meet your stakeholder needs, the richness and value of the original research and insight can get lost in producing something that is watered down to the ‘right wording’. If this is really needed, create a separate budget line to support you to write the stakeholder report.

You should place the value and emphasis on learning, rather than on the delivery of outputs. Raw deliverables are much better and ultimately more useful than over produced tools or reports.

When the output is the goal, we lose all value and meaning in what the intention of the project was at the end.

4. Make the space for your team to learn

Service Design is a knowledge and insight game. If you’re bringing someone in-house recognise that you will gain the most value from them by working with them.

Ensure there is time made available for your team, in particular a product lead, delivery manager or individual closely related to delivering the thing you’re working on to join that team’s journey.

Look wider too, who would benefit from what this team are doing? Any good agency will support you to think about that at the outset, a RACI framework can help with that but it is good to look ahead and make the resource available on your side.

This doesn’t mean looking over their shoulder, but join in their research, attend their stand ups and make sure there are regular show and tells for you to hear about the work first hand.

5. Give us time, commission early

It’s down to an agency to only pitch for a job if they know that they can deliver it. However, I’d be worried if anyone can say confidently they can start within two weeks. Does this business have no other work on? I’m regularly being asked to tender within a two week window and ‘start’ the week after.

We say we can start because ultimately, there are always delays. Contracts, recruitment, finding first dates for meetings, the list goes on, and usually by the time it is all worked out everyone is ready to go, so it usually works out. But it isn’t the best start, it’s good to get that all out the way so our prime focus is the job in hand and our team have had time out from the project that just finished to decompress and ready themselves for the next job.

This could all be smoother.

Try to look ahead in your commissioning cycle by thinking two to three months before you want to start. This means you’ll get a fresh team ready to work on your project without trying to finish off other projects.

Ultimately, this is an agency’s responsibility to be ready to deliver, but just look ahead and commission early, it could make work better for everyone.

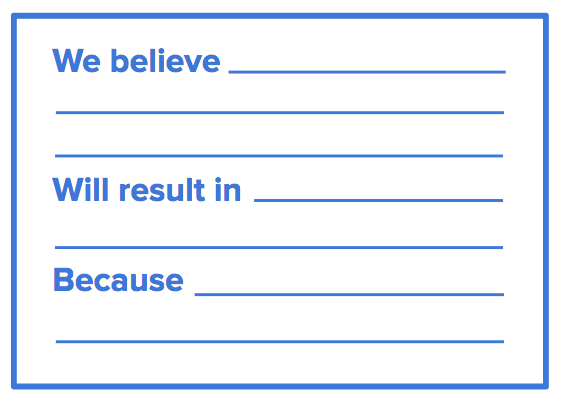

6. Tell us your hypothesis upfront

At the start of any project I map the hypothesis of the project team to gain an understanding of what they think we might find out through the research or what the outcomes of the project might be. It helps us to understand any bias, pre-conceived ideas and recognise any agendas at the table.

It would be really helpful if we knew this when writing a proposal upfront. It helps us to understand what we might want to validate or question from the get go and write a proposal around. Again, any good agency should go through this with you at the outset, however, it is helpful to give the agency more understanding of where your head is at and what they will need to do to validate or break your hypothesis.

7. If you’re trying to win a battle make it clear

Often once we’re commissioned, we find out that our work is more of a political piece than a straight up service design project. This is ok, I understand that part of design can be a democratic tool to validate a user need or perspective with evidence, but it’s good to know upfront. When our work needs to be more persuasive then it’s good for us to think about who is good at that kind of work.

If you aren’t going to be open with a brief, find a way to help an agency understand the wider context of what’s going on. There needs to be budget for some of that understanding and context setting so we can do our work well by understanding the politics of the situation early on.

Design skills can be different from consultancy skills and if you’re going to need a persuasive critical friend, we need to look at our team carefully and think about who right people are to help both surface that insight but then communicate it. That is often not the same person.

8. Beware over delivery promises

We all lose proposals, but nothing stings more than being told someone else promised double what we did for the same budget.

For me, if someone promises you the world for far less than the majority of other bids, this is a red alert.

I’ve been on the commissioning side and been burned early on in my career when someone promised everything.

Ultimately, they couldn’t deliver, and I found they were working all hours to deliver, which meant in turn, the work was sloppy, they were late for meetings and generally didn’t do a great job on any of the project because they had other projects on to bolster their income.

I’d listen to people who push back on the budget, they probably have enough experience to tell you it’s tight. It’s then yours (and theirs) discretion to go forward with the work on the identified budget or bolster it.

9. Remember you’re hiring talent not a process or methods

I’ve lost pitches because ‘our methods’ weren’t clear enough and the competitor had ‘more innovative methods’. Now, I’m not crying over spilled milk here — but it’s really important to remember if you’re hiring designers, you’re hiring good people with experience who can navigate complexity and turn it into direction.

In the modern market of Service Design, it’s pretty easy to pick up a book, learn some methods and dazzle you with the latest buzzwords and methods.

In reality, design means sitting together in a room and working out a route forward by asking the right questions. Those questions come with experience and skills from a design team, not a book.

In commissioning, focus on what they’ve done before, where they’ve done it, what their clients thought, what it helped them to achieve and how they did it. Find out about their process, but don’t weigh this too heavily.

No project is the same with repeatable ‘methods’. Remember it is the quality and experience of the people you are buying, not a process.

10. Don’t expect the answer upfront

We’re exploring together so don’t feel nervous when a design team doesn’t know the answer. The best answer is we’ll find out together but we’re here to guide you.

I’ve been asked a lot for ‘the answer’ or ‘the concept’ in tender documents and the reality is there is no possible way I can tell you. What I can do, is show you where we’re tackled a similar problem but until we get stuck into your organisation and users, I can’t tell you the right route forward.

That is what service design is about, we’re here to take you on a journey to find the right insight and help make a design decision.

This doesn’t mean a design team shouldn’t have ideas. Ask them what questions they would have for you. You want them to be curious and to be ‘thinkers’ who will help uncover the right route forward.

11. Respect the time to think and design

Often tender documents focus on exact days we will ‘deliver’ and what the output is at each stage. For example, for a day of ‘Sensemaking’ what is the output?

The output is a team with the knowledge to design the right thing. But we’re pushed to create outputs that symbolise we’ve ‘done’ this.

I’ve been genuinely queried on ‘time’ that we’ve baked into a proposal for the team to actually design. What they’re doing here is sketching, discussing, researching, prototyping and it doesn’t always need an output.

It seems we’ve forgotten in the world of Service Design that people who are experts still need the space to think.

I 100% stand behind joined sense making workshops and co-design but we need to strike a balance. When we’re not with you, we’re still delivering and sometimes the researchers or designers just need time to think.

I know this point may sound ludicrous, but it happens fairly frequently in commissioning design, to not actually consider the budget to create freedom to just, well, design.

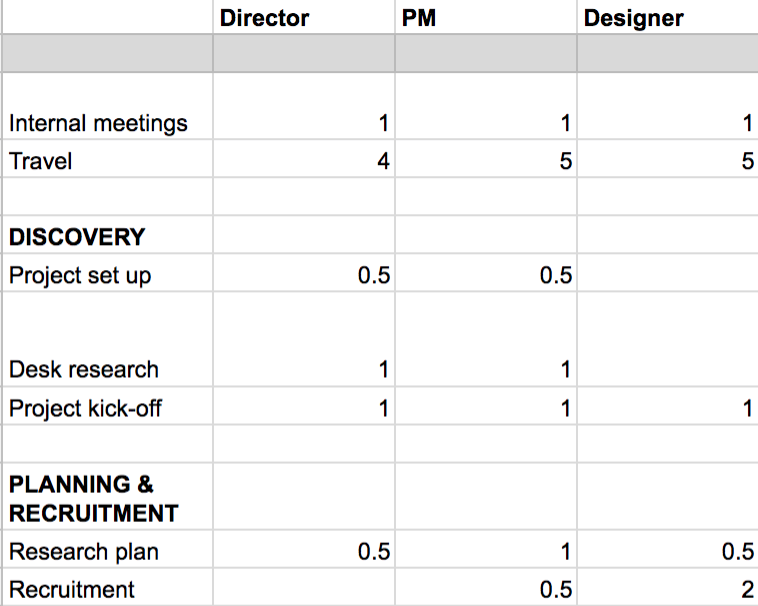

12. Buy time not days

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve spent breaking down a day by day delivery to make a budget work. It’s painstaking, and I’d say 95% of the time changes as soon as we meet the client.

It looks a bit like this;

Phase One

Prepare research framework — 0.5 days

Recruitment framework — 0.25 days

Recruiting — 2 days

Data and platform preparation — 0.5 days

User research x 12 interviews — 4 days

User research interview write up — 1 days

You get the picture. Now do this across a project that requires multiple skillsets, lasts over 12 months and you’re breaking down every day down to 0.25 of days to make a budget work and satisfy the commissioner.

Buy time, weekly blocks of time where people work with you on a problem to solve. It’s better for both organisation procuring and agency.

For example:

(Phase One) Sprint week one

User researcher ( 5 days)

Service Designer (5 days)

Project Manager (2 days)

Ask what each block will focus on and what the outcomes and outputs are for overall phases. Use this flexibly as a sprint based model and pause (through negotiation and trusting contracts) with your supplier, there’s nothing worse than buying dead time. Getting down to the above level of minutia is really a painstaking approach to negotiate how someone will work for you. Re-frame that to how someone can work with you.

13. Clarify what you mean by ‘on-site’

There’s an increase in asking agencies to work ‘on-site’. I totally get this, and we do it fairly frequently but clarify what you mean by this.

When we see on-site requirements we either a) don’t bid as we don’t think the team can travel daily to the site or b) tip the budget on the travel time and expenses to get there.

What I’ve found, is the reality of ‘working on-site’ daily isn’t actually expected as we’re out researching anyway, and our client likes to come to our studio anyway.

During the tendering process, just be explicit on what this means.

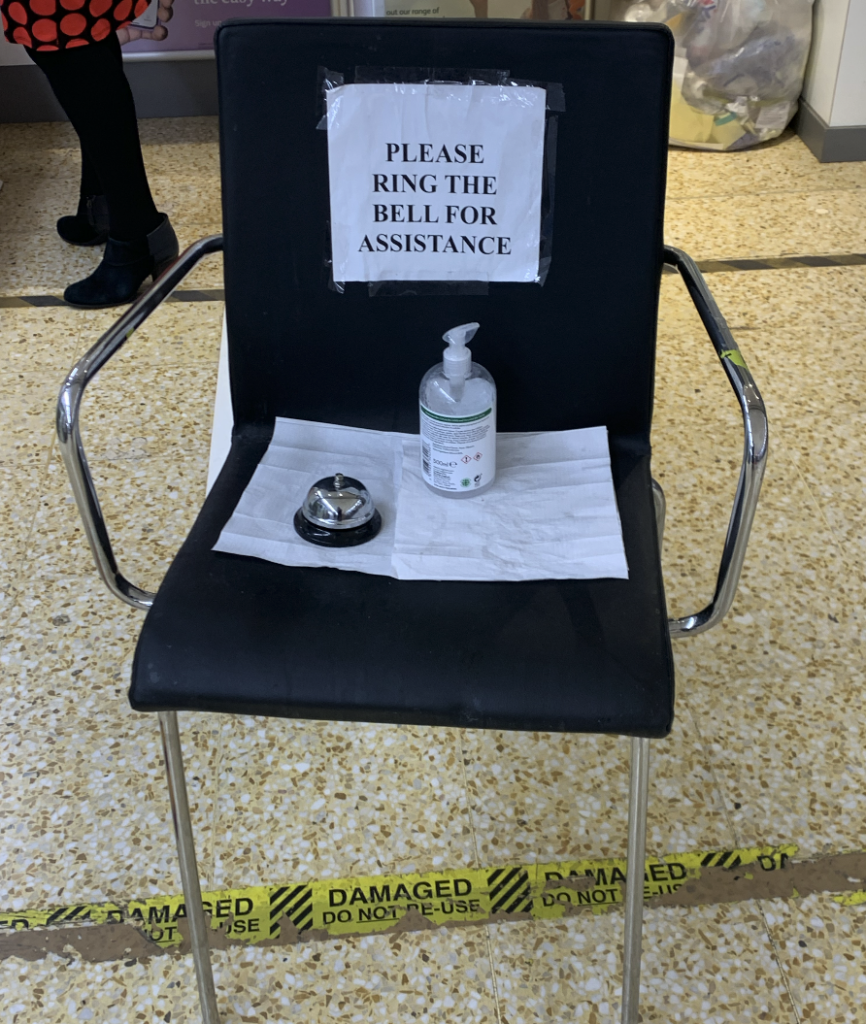

14. Usability test your procurement process

If I had a pound for every hour I’ve spent trying to understand how to respond, reading multiple documents and piecing together the ask, then responding into formatted templates that don’t work, I’d be rich.

It’s painstakingly hard sometimes when PDFs have input boxes that don’t work, codes for projects must be followed to the letter to save a file and there are complex questions without direct asks. It’s like a test in itself and that isn’t even about our response and proposal as experts.

Make it simple. Have a clear ask and make it easy to reply. Try giving your proposal to someone, even a few agencies to have a quick read and get feedback before formally putting it out.

Keep the questions and page expectations relevant to the contract cost.

Above all, make sure your submission forms work.

I have been close to tears at stages trying to fill in badly designed tender forms and that is not an exaggeration. Often it’s another 3 to 4 hours work.

I understand that this is often largely based on using outdated legacy technology to pass over briefs but there’s some simple techniques above in the documentation you provide to the questions you ask that could simplify the process greatly.

15. Tell us if you’ve done this before, and if it failed last time — why did it fail?

It is rare to find a client who hasn’t tried to do a major piece of strategic change before. It’s even rarer still to find one where that was a roaring success. Knowing what came before — what worked and what didn’t — is a great way to help an agency know what ideas or ways of working need to be avoided when delivering a piece of work.

Do people feel burned by a previous agency? Why was this and what should we do to ensure that doesn’t happen?

This is another helpful political question for an agency to gain an insight into who needs to be won over and how.

16. Meet the supplier

Above all, meet the supplier.

An initial phone call with potential suppliers either collaboratively or 1 to 1 is helpful for everyone involved. It may seem time intensive but in the long run will save resource by reducing any confusion of intent from the outset. Additionally, it allows organisations to decide not to respond.

Nothing works better than a follow up meeting to ask the questions you want answers to, and it helps the agency understand the full brief and what you’re looking for.

This can also be done, law permitting, by doing things like holding a supplier engagement call or recording a video of you and your team explaining the work. Overall it can help agencies to propose better teams and approaches.

I’ve written far too many proposals where we’ve been told that we haven’t been successful in the feedback call because what we wrote initially and what the client wanted were completely different.

Words can be a very ambiguous when it comes to mutually understanding a problem space.

I hope some of these are helpful. I don’t want this to sound like I’m crying over spilt milk — losing a tender is a natural part of any business and expected — but we could make it a lot smoother for everyone involved!

If you’d like to add any please tweet me @rufflemuffin and I’ll build them in with a repost.

I’d really like to thank Zoe Stanton at Us Creates for providing some good additions and eyes on this.