Full Stack Service Design is a model to help people break services down into the parts that make them and understand how all of these parts impact the user experience.

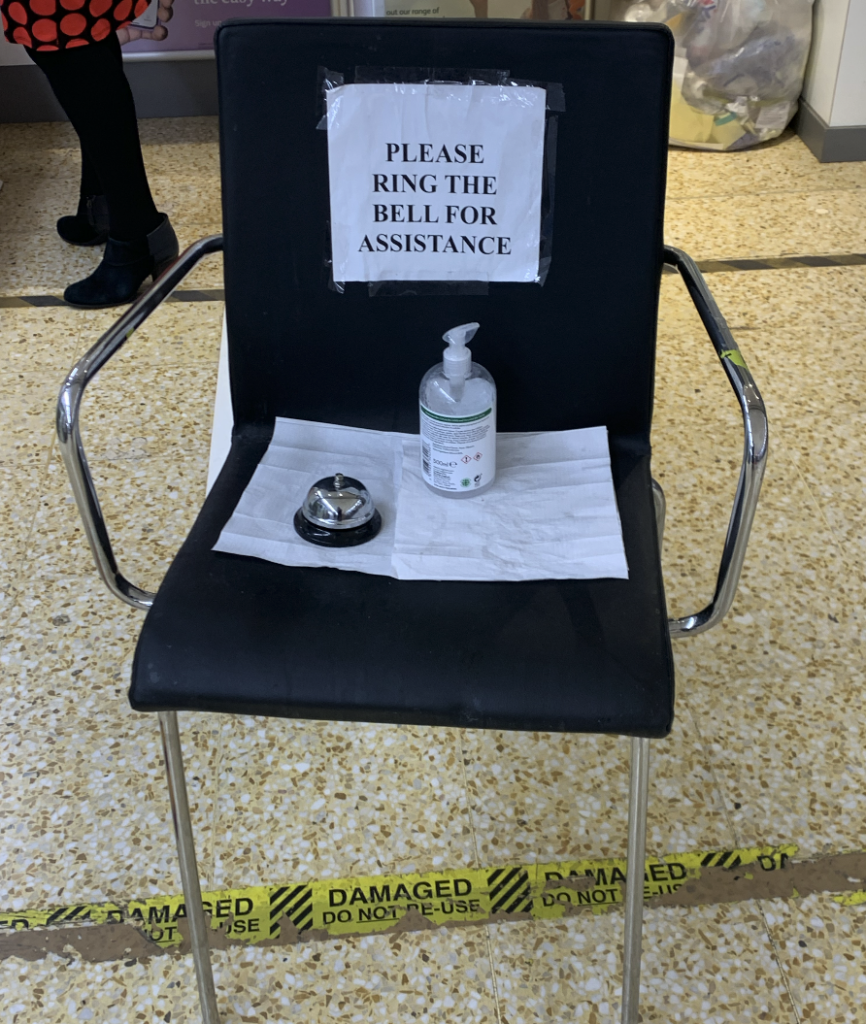

Services are made up of thousands of tiny, often accidental design decisions.

These design decisions are often unconsciously made, in isolation from one another, and without an understanding of the impact they will have on our services or the experience our users will have of that service.

From policy development to metrics & measurements, organisational structures to technical architecture, all of these components – and the decisions we make about them on a daily basis – have an impact on the services we deliver and our ability to meet user needs.

Yet the vast majority of the tools we use to design services – from user journey maps to blueprints – focus on just the parts of a service that a person can see and where we believe we can firmly influence the output of how a service should work with a level of certainty.

Service design is rarely greenfield. Most service design is brownfield most of the time.

The activity of service designing, whether that’s adapting existing services or inventing new ones, usually takes place in an environment where many other services are already live, their structure dictated by the organization that delivers them.

By the time we turn our attention to the ‘user experience’ of the service we are designing, we are often limited in scope because of decisions that were made long before we started. This means that more often than not, we are designing on top of less than perfect infrastructures, fluid organisational models and cultures potentially adverse to change.

The result is that all too often, our good intentions are not implemented because of this imperfect reality that lurks below the surface – the technical, policy or financial constraints, lack of strategic vision, organisational delivery skills or our business model that can scupper even the most well thought through user journey.

It’s easy to think of these things as ‘constraints’ that get in the way of good service design, but these components are the things that design our services, and – just as we would design a machine that builds a product – they need to be consciously designed and influenced so that they themselves can build better services.

When working in a brownfield environment, we need to design how the constituent components of a system – from its rules, policy, culture, infrastructure or design impacts the user experience and how it helps, or stops meeting user needs and/or desired outcomes.

Just like a mechanic can navigate, diagnose and fix a car’s engine with the help of part specialists, we need the capabilities to navigate an organisation or system, diagnose the parts that are blocking a service meeting user needs, and collaboratively orchestrate a strategy alongside domain experts on how to improve this.

Service design isn’t an individual role, it’s a team sport. This is about ensuring the layers of an organisation consciously recognise their role in making the right decisions that will enable an organisation or system to meet common goals, user needs and service outcomes.

Introducing Full-Stack Service Design, a model to help us understand what the components of a service are and how they affect the user experience

This model helps to identify what the components of a service are, and how they impact its design.

Just as a product designer making a chair will understand the malleability of materials they are working with and the manufacturing processes to go from raw materials into a product someone sits on, this model will help you to navigate the physical and invisible materials that make up services.

The materials that our services are made of form a series of ‘layers’ – from the veneer like surface layer a user sees – the service itself – to the infrastructure that this service sits on, the organisation running that infrastructure, the intent that drives that organisation, and eventually, the culture that leads to the creation of that initial intent in the first place.

As we tunnel back through these layers, we see how each preceding layer has an effect on the next. Like the layers of the earth’s crust, each reliant on the next layer down for it’s stability until we reach the core, that affects them all.

These layers form a ‘stack’ of things that we need to think about when designing services – the full stack of service design.

The 5 Layers of Full-Stack Service Design

1. The Service

The things a user sees and interacts with.

The service is made up of the user experience and business processes which enable the value for the user to take place

For example if you want to withdraw money from a bank account, you will interface with a website, app, or phone and be taken through processes to ensure you are who say you are

2. The Infrastructure

The things that enable our services to be delivered

Infrastructure affects the way we build our services because services rely on the technology that is used to deliver and maintain them over time.

For example: If we build our service on a system that needs to process user records in batches, that might mean that our service can only be available during the day time as we need to allow our system to process new users overnight

3. The Organisation

How we organise ourselves to make decisions

Our organisation affects the way we build our services, because the way they are structured can enable or disable decisions being taken.

For example: If an organisation has a structure that is made of lots of small, independent business units with separate budgets that aren’t able to collaborate, that organisation will find it disproportionately difficult to provide a service that cuts across different business areas that meets a user need.

4. The Intent

The reason why we provide services

Our intent affects the way we build our services because the things we want to achieve as an organisation drive the creation of services. It can be common for organisations to forget what that intent is or fail to work out how to deliver it in the real world.

For example: An organisation that was structured to avoid risk often finds it difficult to innovate in a fast moving market.

5. The Culture

The conditions that affect how we make decisions

Culture envelopes all the layers of what makes up services because it shapes how we make decisions and act as individuals and collective entities. From the autonomy staff have to how authority works, culture shapes how we design and deliver services based on our shared morals and beliefs.

For example: If an organisation provides support to users and believes they are the expert, they are unlikely to empower the user to solve a problem. This can be a view held because of organically aligned beliefs, nurtured by the organisation’s cultural efforts.

These 5 layers can be used in any context, whether actively re-designing services, or reviewing how your part of a system can think about better meeting user needs and service outcomes. Think of it like the tv programme ‘How it’s made’, but for services.

I’ve written a guide on different ways to use this model. If you have other ideas, I’d love to hear about them.

A service is something that helps someone do something they need to do – be that to pay tax, book a holiday or buy a house. Services are designed (intentionally or otherwise) to deliver an intended outcome as defined by the organisation providing it.

When someone is using a service, we might refer to them as ‘a user’, and the experience they have as the ‘user experience’. We might replace ‘users’ with other more specific words like ‘patients’ ‘visitors’ or ‘residents’ that reflect the relationship that our user has to our particular service.

When we talk about someone using a service, we can also mean people who are delivering that service, because that person often needs to use parts of your service, even if they are doing so to provide a service to someone else

Services are made of the things that our users see and experience themselves – their user experience and the things they don’t see – the business processes that we use to run those services.

The things a user sees and experiences are made of lots of small interactions with your service. This user experience is designed to orchestrate someone to do the thing they set out to achieve, like depositing money, applying for a driving license, managing or improving their health. These interactions might be made of letters, text messages, phone calls or emails – what unites them is the overall effect that they have on what a user perceives and feels, or what they ‘experience’.

Some of these things are in direct control of your organisation because you will design and deliver those things yourself (like, for example, the booking and check-in experience of your hotel), but other parts of your user’s experience will be outside of your control (like the fact that your user was late to check in because there was a lot of traffic on the road).

How good your user’s experience is will be dictated by how well the different parts of their experience are designed to work together, and how well they are able to use these things to achieve the outcome they set out to do, despite the surrounding circumstances.

How does the user experience affect the service?

In markets where there are competitive options, a poorly designed user experience may put users off choosing your service, even if your service is the same as other providers.

Poorly designed user experiences where users need further support to understand how to use your service can lead to an increase in backend servicing of the user and in turn, greater cost of delivery.

If the user experience of the service is not designed to be accessible, many users will be unable to interact with your service and get the desired outcome they’re seeking by using it.

Questions we can ask as leaders

- What are the outcomes we want our services to deliver (policy, user needs, organisational)?

- Do we know who our users are?

- Whose needs do we want to meet?

- What are our services?

- Do we know what good looks like for users?

- Are we delivering the right services, do they meet user needs?

- Do we need to stop or radically redesign any of the services we are delivering?

Questions we can can ask if we work with this specific component

- Have we designed all of the elements of the user’s experience to work, regardless of the circumstances outside of our control?

- Is the service inclusive and accessible to everyone that will use it, including all touch points of the service?

- Does our branding align and communicate what our service offering does in a way users need it to?

- Is the connection between services that sit out of this domain easy for users to navigate?

- Have we resourced our service appropriately for the demand?

- Is there a service manual on how to deliver the service available and clear?

- Do we know where the service could fail and have a designed pathway to recover from this?

- Can users feedback purposefully on their service experience?

- Do we have access to feedback and are we using it appropriately to improve our service?

- Is there a pattern in the questions we are being asked by users for further information or common complaints, and what can we learn from this?

Information we need to understand before we start designing

- What is stopping the user experience from working for people?

- Do we have data on how our service is performing?

- What does the end-to-end user experience feel and look like?

- Are we meeting user needs, do we know what they are?

- Do our users understand what our services do?

- What are the steps needed to help a user complete a task?

- What information do we need from them to complete a task?

- What are the touch points needed to orchestrate helping someone to reach the intended outcome?

- What are the design principles that ensure the service is consistent?

Business processes are a series of actions we take as an organisation that enable services to take place.

Some processes are explicit in the user experience, involving a combination of interactions between staff and users, for example, checking someone into a hotel. These are commonly known as the ‘front stage’ processes.

Others are automated or invisible to users, like a background check on your finances if you’re applying for a mortgage or health and safety processes to ensure what is being delivered meets safety standards. These are commonly known as ‘backstage’ processes.

Other business processes are not directly related to powering the user experience but facilitate the organisation or system to work collectively in order to facilitate all of it’s services, for example – internal payroll, or deliveries of goods.

Business processes usually have artefacts that support staff to understand how to deliver services. These things might take the shape of manuals, online learning resources, process diagrams and in-person training sessions. Some of these even become learned and imbibed by staff over time.

When business processes are not designed well, they can be expensive to provide, stop users from getting the support they need, or force them to become experts in negotiating your complex processes. Many poorly designed business processes end up being hacked by staff to deliver work more efficiently which can end up supporting users better but also potentially putting them, or staff, at risk.

Processes will usually incorporate elements of compliance, or health and safety to ensure staff and users are kept free from harm, for example, a process might be put in place to keep users data safe and meet data protection regulations. These are usually reviewed and audited by organisations or sometimes externally accredited by ISO standards. Understanding these standards will help teams know what needs to be designed into the processes that power services.

How do business processes affect the service?

Business processes can increase or decrease the time it takes for your user to do the thing they need to do

Business processes can be designed with varying degrees of flexibility, either enabling or disabling staff from performing certain activities that help your user to achieve their goal

When exposed enough to users, complex business processes can force people to become experts of complicated systems and language.

Poor business processes can lead staff to ‘hack’ or creating workarounds that make the service easier to deliver for staff, but that could potentially put users at risk

Questions we can ask as leaders

- Can our staff effectively deliver service outcomes and meet user needs?

- Does our propensity for managing operational risk stop our staff from delivering the right service for our users?

- Are we asking humans to do the work of machines and if so, can we utilise these skills for more purposeful work?

- Do we have clear resources that enable our staff to deliver a consistent user experience that meets outcomes?

Questions we can can ask if we work with this specific component

- Are the business processes we have in place inclusive and accessible for staff to deliver? Or are our staff forced to create unofficial workarounds to help our users?

- Do our business processes have review processes in place?

- Is there a continuous improvement approach implemented for making changes to our processes? If so, how engaged are front line staff in this?

- What is the cost of delivering the user experience we want to deliver and can it be reduced or delivered more efficiently?

- Is there any duplication in our business processes, and can we reduce this?

Information we need to understand before we start designing

- How do restrictions in our background business processes affect the user experience?

- What processes go outside of the organisation and are reliant on partners/others in the system?

- What organisational processes and policies sit behind the business processes that support the user experience?

- What safety or other standards must the service adhere to and how does this affect our business processes?

- If business processes are visible to users, are our user’s forced to learn how these work in order to use our service?

Services are built on infrastructure that enables them to run. Sometimes this infrastructure is visible to users, but most of the time it’s behind the scenes powering the service to help users, both staff and members of the public, do what they need to do.

Most services, whether they’re experienced online or offline by our users, are powered by some kind of system or set of technologies.

Users tangibly interact with technology all the time. We log into digital services, we buy tickets in train stations from machines, we pay for groceries using a debit card. These technologies have a direct impact on our experience of a service, however just because users don’t interface directly with a piece of technology, it doesn’t mean that this technology doesn’t have a huge influence on the service.

Emergency call handlers use interfaces to deploy ambulances, clinicians document patient notes in systems, banks call up your financial data to check for fraud. From documentation to decision making, we interact on a daily basis with the technology that powers services, whether we know about it or not.

Your choice of technologies, how they work together to produce a system that supports your service can dictate the edges of what is possible, and what is not in the services we deliver.

Your decision on what technology to choose and how it is managed is an important one, and how much control you have over it directly impacts your service. Systems and physical hardware can be managed and developed in-house by a skilled team, out-house through a contractual arrangement with a supplier or in a blended model where some of it is managed in-house with more complex components of it out-sourced.

Understanding what technology powers what parts of your service, what those technologies are capable of and how easy they are to change is key to recognising the constraints and possibilities of future service design.

How do our systems and technology affect the service?

If staff can’t easily use the devices and systems provided to them to do their jobs, it negatively affects the time they can spend on delivering the service

If staff have to use multiple systems to deliver a service, it can impact the time taken to deliver it and result in less users being supported directly

Our ability to change technology systems quickly impacts our ability to be responsive to user needs

Contractual agreements on the technology estate affect our ability to update products and make changes to the user experience

What and who we choose to run and design our services on or with, technologically speaking, can both enable or restrict the freedom we have to integrate with other systems

Questions we can ask as leadership

- How does our technology stack need to meet new and emerging needs?

- Are we getting the best value for money from the model we use to operate our technology provision?

- Do we have the right contractual renewal dates for technology and systems? Are they so long in the future that our providers aren’t incentivised to change, or too short meaning there’s too little value in the contract for improvements?

- Do we have the right in-house capabilities and skills to manage our technology and systems, and continuously improve the platforms and systems over time?

- Do we understand the options for our technology and systems estate?

- How can technology help us improve meeting service outcomes for our users?

- What systems does our technology and data need to connect with to power the services we run or should run?

- What technology stack do we need to best operate our services and plan for future improvement and changes?

Questions we can can ask if we work with this specific component

- What is the experience of internal users operating the platforms or systems and can it be improved?

- Are there policies which stop the use of technology that impacts on the user experience?

- Do we have risks mapped around our technology estate and mitigation strategies?

- What tools do staff use to communicate?

- Where do we store core organisational knowledge?

Information we need to understand before we start designing

- What are the platforms, systems and digital collateral involved in administering and running this service?

- What services run on what platforms?

- What is the roadmap for technology in the organisation?

- What are the platforms and hardware staff use to administer the service?

- What contractual arrangements are in place for delivering our technology systems and hardware? Service level agreement?

- What are the operating costs for our technology running the service(s)?

- What are the existing capabilities of our technology stack?

- What technology do staff need to do their job well?

- How are the systems hosted and where is data stored?

- What is the relationship between customer and supplier if the system is outsourced?

- Are our systems interoperable with other systems we need to talk to?

In most services, ‘data’ is information in a form suitable for storing and processing by a computer, sometimes open for anyone to view, but mostly closed because it is sensitive, personal or owned by an organisation.

Data can be qualitative and quantitative. Qualitative data is non-statistical and descriptive, typically unstructured or semi-structured in nature. Text documents, audio and video recordings and images are all examples of qualitative data.

Quantitative data on the other hand can contain all sorts of information about us like our names and addresses, and when this data is combined, can be used to identify a bigger picture.

Data can be produced by our users, for example, by inputting information into a form, or tracking our daily exercise. It can also be produced about us, for example, by a social worker registering a concern in a system about a child.

Qualitative data isn’t typically easy for statistical analysis but instead can be categorised manually or by labels or common attributes. Quantitative data on the other hand can be counted, measured, and expressed using numbers. We might not be aware that we are producing this data- like browsing history, or the tracking of where we’ve visited with our phone in the background. What is important about quantitative data is it is typically structured to be easy to analyse and called upon through various mechanisms.

When it comes to using data to design services, there are four things we need to think about

- How we document and standardise our data

- How we use and exchange data

- How we use performance data to inform our decision making

- Safety and privacy

Documentation & standards

Data standards are the rules by which data is described and recorded. In order to share, exchange, and understand data, we must standardize the format as well as the meaning.

Services can talk to each other through data exchange, but only if we standardise how we record that data and make it available.

Standards are important because they enable different sets of data to be used together, for example, a user’s name and age that might be recorded in one part of your service is then able to be used alongside that same user’s location that might be recorded elsewhere in the service

Standardised data also relies on guidance and documentation for how we record and share better quality data.

Transactions and exchange

Data is only valuable if we use it to do something. Data powers services and enables multiple types of user interactions to take place. These exchanges utilise data that is available to call upon and can work from multiple sources once data is standardised.

In order for data to be used within our services, and exchanged between all of the different parts that need to use it, we need to establish rules on what to share and how to share it.

One of the ways we enable our systems to talk to one another across organisational, geographic or sectoral boundaries is to use APIs. This stands for Application Programme Interface.

Think about when you book a holiday online. Many sites will aggregate thousands of flights and destinations which you can filter based on price, or location, or available hot tub! Many services use third-party APIs to collect flight and hotel availability from providers and to confirm the trip with the provider they sourced it from.

Performance

To understand if we are meeting service outcomes we need data. Performance data captures insight about how our services are performing. This is captured in a variety of ways from manual questionnaires performed at stages of the user experience, for example a charity assessing how well people are when they enter and leave a recovery service to automated data like a municipality collecting how many cars are on a road through sensors.

Access to this data is vital and our ability to analyse it against our performance indicators for a service is important. Often this data is part of a reporting mechanism so being able to extract it in a meaningful way for internal or external reporting can matter, and in the most efficient way possible.

Safety and privacy

Almost every aspect of our service will require some collection, storage or use of data. At each of these points it’s important to consider how safe and ethical the use of that data is.

Data is a material and how we store it, name it, use it, all needs designed to ensure when we design a service that enables a user to do something, it enables them to do so with ease and does not conflict with existing regulations that protect users like GDPR and the Data Protection Act. Baking in privacy by design features and considering data as a material that powers services, we should always actively interrogate the consequences of the services we design and if there any unintended consequences that would be considered a breach of someone’s rights.

How does data affect the service?

When data is not interoperable because of lack of standards or guides on format, it can result in manual processing leading to mistakes and failures in the user experience

Without considering the consequences of how user’s data is presented, we can create negative impact on the user experience

Data can define what users see and interact with in the user experience through profiling perceived interests or needs

We can improve the user experience by reviewing what is and isn’t working from data

We can use data to improve realtime user experience

Data storage can define how we build and launch services and at what pace

We can use data to build up a better picture of users and proactively support them

Privacy by design currently causes friction in the user experience, adding more steps to users transacting in services

Aggregated data can help the wider system learn about trends and needs and govern with more user centered policy and outcome frameworks

Without the right data, we can’t report on and understand our service performance

Questions we can ask as leadership

- Does our data tell us if we are meeting our user’s needs?

- What value does our data have?

- Can our data be opened up?

- Is our data in a format we can access it easily and build services on it?

- How reliable is our data storage?

- If we outsource our data storage, who will have access to it?

- What emergency and post-emergency processes are in place to protect our data?

- Do we have the right permissions for how we handle data? Which laws, regulations and industry guidelines do we need to comply with?

- What are the costs of our data model?

- What can we learn from the data we have?

Questions we can can ask if we work with this specific component

- Is our data stored in a format that fits with common sector or industry standards?

- What data are we handling manually that could be automated?

- What data is needed at each stage of the user journey to power it?

- Are users aware of how their data is used?

- Can user’s data be deleted and is it easy to do so?

- What data we collect is classified as sensitive and what roles are allowed permission to see this?

- Do our data analysis tools (e.g algorithms) put any users at a disadvantage?

- Who is responsible for reviewing our performance data

Information we need to understand before we start designing

- What data is powering our services?

- What data do we have access to?

- Is the data we’re collecting help us meet user needs?

- Is there any data we do not need and can stop collecting?

- What systems does our data talk to, or need to talk to, to meet user needs?

- What standardisation of our data can we implement?

- What data is needed to improve our service?

- In what format is data stored and how do we ensure it is interoperable across systems (e.g APIs)?

- Where can we automate data input?

- Who needs to access our performance data and in what format?

Services are shaped by the organisations that create them.

Just like how a product is shaped by the machine that produces it, the way we construct our organisations or collaborative arrangements to design, deliver and maintain services affects the user experience.

Our mental models of how organisations or organising should work often create constructs that our services inherit, making users do the hard work to navigate the bureaucracy of organisational designs.

Governance drives organisations and brings people together to make decisions. How it is run, what data we use to make decisions and who is involved all impact on our services.

Importantly, governance outlines not just how decisions are made, but the rules of who might be involved in taking decisions, who has authority for those decisions and who is responsible for these when they happen.

When governance is done well, it helps us to make sure we’re delivering our mission, monitoring risks and delivering the services we should be. Without governance of some format to monitor and challenge performance and risks, organizations can put their sustainability at risk and the services they deliver.

Governance takes the form of varying processes, rhythms and rituals that bring together people at varying levels of seniority – from boards to team meetings – to take collective decisions. This usually comprises scheduled meetings that bring together information and data in varying formats and the decisions being taken within these.

To make informed decisions you need data and knowledge. Good governance considers what type is needed to make informed decisions about the services being delivered and the sustainable operation of these. The most important piece of information to include in any governance is information about the end user and what effect any decision that is being taken will have on that user.

It’s important to recognise that whilst governance is run as a set of formal events and structures, the influence on decision making can often come in between the margins of meetings through conversations. The importance of relationships and power must be recognised amongst the formality of governance.

Understanding how governance comes to life in your organisation, what relationships drive it, when key moments take place, who is involved and what kind of data is being used to drive decisions within a given governance structure is key when you’re considering the redesign of any service.

How does governance affect the service?

How much autonomy we have to make decisions on behalf of users can impact our ability to be able to respond quickly and proportionally to the things we find in user-research and improve our services

Not having performance data on services in the right forums can impact the effective design, delivery and maintenance of a service

If services aren’t properly governed, they can quickly become inefficient or unprofitable, leading to the discontinuation of services

The sustainability of a service is based on the strength of an organisation’s governance. At an organizational level, if your governance is not effective in marrying up the supply and demand and the balance of funding of your services, there is potential for services to suffer, leaving users in potential danger if it is a critical service for them

The user experience can be affected by poor decision making governance when there is a lack of understanding of what it takes to make, build and deliver services. This can lead to setting short time frames to deliver services

Questions we can ask as leadership

- What governance do we need to effectively run and protect our service users, both as our organisation and with our wider network of partnerships?

- What are the decisions that need a senior level of sign-off? What can and should be delegated to the front line of our organisation to decide?

- Do we have the right data to make informed decisions about our organisation and services?

- Who should be involved in making decisions around our strategy?

- Is service performance part of our governance model?

- Have our decision makers experienced our services recently?

- Is equality and diversity part of our governance?

- What are our organisational risks and who is managing these?

Questions we can can ask if we work with this specific component

- What regulatory or legal obligations do we need to meet to govern ourselves effectively?

- Do we have the right data and information to report effectively on our performance?

- Do we have governance in place to review any partner organisations ability to deliver and sustain our partnership together?

Information we need to understand before we start designing

- What is the organisational governance model?

- Where are critical decisions made that affect the service outcomes and user experience?

- What are the sector or organisational key regulatory and legal obligations to make in relation to the services they deliver?

- Where are the informal relationships that influence decision making?

- Does the governance help or hinder teams to make decisions and take action where needed?

Most services are shaped by what money or resource is available to invest in and run them. This money can be provided by a range of avenues, directly from customers to public finance models where organisations work under contract, commissioners, annual letters or targets.

Finance is the management of money and includes activities such as investing, borrowing, lending, budgeting, saving, and forecasting. What an organisation invests in, often centres around their forecasted budget. Forecasts and budgets are usually cyclical and in many traditional models run on an annual basis with the backdrop of a forecast painting the best and worst case scenarios.

Financial budgets and forecasts will usually be aligned with some form of organizational strategy so recognising where and how these decisions are made, and how they are signed off, will help release investment when you’re trying to improve a service.

Financial budgets and targets are usually provided to departments, teams, services or functions of an organisation that outline what they can spend on delivering their service, commonly with targets on what they should make or save.

The type of money or funding an organization can also come with constraints. External funding can often come with conditional outcomes attached to it, stating what an organisation should deliver or spend it on. Some funding is to specifically fund service delivery. Some are conditional for an organisation to develop it’s governance to be able to deliver services well. This can often result in organisations building services specific to funding they have received and eroding their original central offer they set up to deliver or investing in short term needs, over longer term infrastructure.

Funding is rarely stable and can also increase and decrease dramatically in quick cycles depending on external factors. When there is increased need for a service, for example in a pandemic, funders may invest in increasing provision quickly. This will drive new services and increased capacity for meeting needs, however when over, finance can force these to close down as the programme of work finishes.

The balance sheet is a key touchpoint of an organisation’s decision making. Institutions regularly meet around maintaining a clean balance sheet indicating they have little or no debt, or if there is actual debt, that the risk is managed and will be recovered. A balance sheet is the summary of the financial balances of an individual or organization, no matter what kind of formal structure exists and in short, covers their assets, liabilities, any shareholding equity at a specific point in time.

A clean balance sheet means ensuring a healthy level of available cash (liquidity) to flexibly fund operations and save up for what the Brits call, ‘a rainy day’, where you have to recover from something unexpected happening. This is about being fiscally responsible and ensuring there is a healthy level or profit to reinvest back into running the organization, or spending to the limit of what has been outlined for an organisation in their financial envelope or ensuring in a charitable context there is a healthy level of reserves maintained.

It’s important to recognise that many decisions on how resources are allocated – whether that is expenditure for service provision, development work, or ongoing maintenance – will all come back to a spreadsheet. In larger organisations making decisions might be taken by a business or finance team who are overseeing a business case for a specific department, and will make a call on expenditure on a case by case basis. In small organisations decisions might come back to a basic live spreadsheet where examination on spend is a literal line by line outline of expenditure. The numbers may be hugely different from £100s to multi-million contracts, but the question is always the same – can we afford to do this, and what is our return?

Depending on motivation, corporation type and business model, an organisation might emphasise profit, breaking even, or spending funding they receive wisely with conditions, like a grant.

This might mean that financial decisions take the form of resourcing decisions or decisions about time and focus of a team. It’s not money that’s the asset here, it’s people’s time but it’s still a resource that powers a service.

Understanding basic economic concepts can go a long way in recognising how services are costed, financed and sustainability can fluctuate based on external factors. Profit and loss, cost of delivery, EBITDA ( Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization), return on investment, scarcity, supply chain are all terms and concepts worth learning so if in the position of making a business case to invest in services, you can talk in the language of the balance sheet.

All of this is important to recognise who and what is driving decisions in terms of how an organisation invests. How systems and organisations finance services impacts on the ability to sustainably deliver them and improve them overtime. This includes non monetary based investment, for example where to focus internal resources.

An organization’s annual or time based budget typically outlines where resources will be spent and is sometimes signed off by external stakeholders or decision makers, like a board of trustees. Understanding when and how these decisions are made is important if you need to navigate or pitch for funding to develop and deliver services.

Further to how funding works, it’s important to think about how an organisation invests. An organisation can choose to invest their finances and resources into the technical systems that power a service, the user experience of a service, the staff who deliver it, the security of the service. There are many spinning plates to invest in keeping a service running before considering investment in updating or changing it.

If an organisation has money in abundance, it may still not choose to invest it into service development. An entity can choose to manage its finances to focus on varying different outcomes. They might choose profit and deliver a minimum viable service, or a service just good enough for users. It can choose to use profit to invest in research and development, and improve its services overtime. An organisation can choose to focus on increasing turnover by developing more services in the marketplace or choose to retain existing shares of services and continue to deliver their service. Conversely, they can choose to deliver less.

Finance, understanding it and how organisations take decisions around it, is central to service design.

How does finance and resources impact on service outcomes and the user experience?

If there is no available finance or cash fluidity, an organisation cannot invest in updating or improving its service

The constitution of how an organisation is set up and its goals will affect the decisions made on service expenditure and investment

The timescales for service improvement to meet user needs is reliant on being programmed into a financial decision making cycle and forecast, and ultimately the timing of service improvements may revolve around annual budgetary sign off

Emergency funds at a time of increased need can create a dependency on services which can result in issues when this extra money is taken away

Supply and demand of materials to deliver a service and their costs will impact the bottom line of an organisation and change their capacity to meet the scale of demand, positively and negatively

Funding, if not designed well, can limit cross organisational, departmental or geographic boundary work because it limits where it can be spent

Service decisions can be driven by budgetary cuts that are outside of an organisation’s control

The promise of finance in return of future profitability can drive decisions on how a service might be designed to save money or make profit

The conditions and outcomes attached to financial investment will dictate what kind of resources can be focused on service improvement or purchased

How a service is designed may be dictated by how it is assessed for financial gateways of spend controls

The spend controls set out in an organisation or sector’s legislation can stop a service from progressing into implementation

Questions we can ask as leadership

- What do we need to invest in year on year to maintain our services?

- Do we know if our services need investment to meet user or customer needs?

- What risks are there in the cost of delivery of our services?

- How is the service portfolio financed and does this affect the user experience?

- What, if any, are the savings targets for the organisation and how does this affect the user experience?

- What is our research and development budget for improving our services?

- Can resources be aligned across departments or silos to deliver an improved user experience?

- What do we need to financially plan for in relation to our services (emergent technologies, user or societal needs, threats)

Questions we can can ask if we work with this specific component

- Does the funding model support services to be designed across organisational and system boundaries?

- Is there a business case process or forecast review we can align our service improvement asks to?

- Can we make cost savings through more effective or lean delivery?

Information we need to understand before we start designing

- What investment does the service need to ensure it is secure overtime?

- What is the current cost of service delivery?

- What does our service design cost to run if implemented?

- How much does this service or service portfolio cost to deliver?

- What is the cost of our service redesign?

- What external factors might increase or decrease the cost of service delivery?

- What are the key financial outcomes/impacts this service or product need to align to?

- What does a business case need to include to ensure investment?

- What is the organisation likely to invest in, what information will de-risk this investment?

Procurement and supplier management involves buying goods and services that enable an organisation to have the resources, equipment and people to deliver their services.

Procurement can refer to the final ‘purchase’ but can also refer to the process of defining a need, going to a market, choosing suppliers and signing contracts for delivery.

The procured services can be both directly and indirectly connected to the service the user interacts with, for example organisations might procure research services that help inform their organizational strategy or they might procure entire end-to-end services for users and the touchpoints they interface with.

Procurement can form a large or a small part of your organisation’s ability to deliver services, with some organisations being set up to handle the procurement and running of services entirely through external providers, and others delivering their services entirely in-house with minimal help brought in.

Most services run at scale will have some kind of interdependency on an outsourced supplier which is usually technology related, and organisations have to make a decision based on their finances, skills and capabilities whether to deliver services themselves or utilise external suppliers to help them. Whilst there is no right answer that will fit every organisation a balance needs to be struck between the speed of initial delivery (which is often faster with an external supplier), the speed to spin up a service and the long-term sustainability of the service.

Some organisations allow teams to run their own procurement, meaning the individual who will be responsible for the successful delivery of a supplier’s contract will be at the helm of the procurement and see it through. However, in many instances, a scope of work or outcomes can be translated by procurement and legal departments to ensure it can go out to market. Sometimes the actual needs of a team or department can get lost in translation during procurement because of the need for legal definitions or domain expertise not being readily available in the procurement team.

This misunderstanding can continue once a supplier has been chosen and a legally binding contract developed at the end of a successful bidding process which can include targets, incentives and service level agreements (SLA’s) that can shape the way that this supplier works and therefore the service itself is delivered.

With any outsourced component, we must ensure that suppliers will consider user needs in the way they work and ideally, commit to iterative development and improvement of the service over time. Unless these needs are thought of at the outset of procurement, it’s all too easy for organisations to purchase an external supplier’s systems at a low price and feel like they’re gaining value for money but find themselves later in difficult circumstances when the costs to have simple changes made mounts up.

From setting the anticipated outcomes and needs, to how you engage with suppliers, the criteria you use to assess suitability of a supplier can be tailored to emphasise a focus on user needs and iterative development. This is far from the norm of outsourced contracts but a shift that is being called for. Most procurement exercises list refined details on outputs, lengthy pre-defined features and unshiftable delivery dates because it is easier to manage and review performance, however this is usually inadequate for modern and agile ways of developing and running services to be able to respond quickly to changing needs.

Getting the contract right, arrangement around collaborative working and expectations, continuous improvement needs, and integration with your existing infrastructure are all important considerations in the procurement of external support to run services and setting the conditions for how you will manage and work together with suppliers.

On the flip side, if choosing to run services in a more blended or in-house approach you need to be sure you have the right finance available to continuously resource the maintenance, development and running of services through skilled teams and staff.

How does procurement impact service outcomes and the user experience?

If procurement focuses on outputs, not outcomes it is likely the service will not meet user needs over time

Service level agreements (SLAs), developed during the procurement process will dictate if and how your service can be improved, timescales for requested changes and what happens if something goes wrong which will impact your user experience

The contractual agreement will outline costs for changes to be implemented to your externally provided service which you may or may not be able to afford

If your external service providers are not adequately audited, they may pose a risk to service continuity if you externally outsource and they hit hard times

Procurement must ensure that suppliers will be able to integrate with existing systems that services are run on and meet any integration post system upgrades that are in the pipeline, or costly development may be needed and disrupt service continuity

Without clear design principles in place that suppliers must meet, suppliers may not consider user experience and user needs as highly as you do resulting in an inaccessible or poor user experience

A blended mix of service providers that make up a user journey may cause confusion for users if the name of services or brand changes during their experience

How you score your potential suppliers and the criteria they must meet could alienate certain organisations from bidding for your service

Questions we can ask as leadership

- What services do we need to outsource, and what can we confidently deliver in-house?

- What skills and internal capacity do we need for the future to ensure our organisation can respond to changing needs?

- Can we run a joint procurement for the development of key infrastructure with other organisations and share the investment?

- Are we getting the best out of our suppliers?

- Do we need all of the modules a supplier is selling to us and can we reduce costs of contract?

- Do our procurement, legal and commercial teams understand user experience design and how to make this part of procurement and contractual arrangements?

Questions we can can ask if we work with this specific component

- Do suppliers have ample opportunity to learn about our service vision and outcomes in the procurement process?

- Are there clear user needs for an outsourced supplier to meet, or is it within their scope of work that they will work with or for you to define these and deliver a service that meets them?

- Does the supplier team have a process for meeting user needs and continuously developing services?

- Is this supplier in a secure position to deliver this

- Does our SLA ensure suppliers have a well designed experience for users if the service fails or stops working and recovery model in place?

- Can we frame our procurement around outcomes and reduce output language?

- Does the financial model, payment agreements and contracts ensure we can continuously improve our service to meet user needs?

- Do our contractual agreements discuss end user experience?

- Should we have users or key staff involved in the procurement process?

- Do our contracts outline outcomes that focus on the end-user experience?

Information we need to understand before we start designing

- What is the current ecosystem of services run on and by?

- What are the key contractual agreements and/or SLAs in place for this service(s)?

- Are any of the contracts flexible in changing the agreements?

- What does a user centered SLA look like for this service?

How we work as an organising structure, and how we design – whether consciously or unconsciously – our organisations into departments and teams can often dictate the design of our services, structure and processes for users.

We’re used to hearing about siloed organisations being bad. In truth, most organisations have silos of one kind or another and they can be useful for ordering complex work and systems.

More often than not though, these useful silos are a double edged sword – helping to deliver complex services, but at the same time preserving that same complexity in hard-coded team structures and job roles.

These silos can easily also lead to breakdowns in the user experience, and create confusion over who is accountable at each stage of a user’s journey through a service. This can lead to a fragmented or disjointed user experience when these organisational seams become visible to your user, forcing them to learn the organisational structure and its codified language to use the service.

But it’s not just organisational silos that affect the way we design services. We can talk about ‘organisational structures’ in a few ways.

There are official organisations – those registered in a country as a business, a charity, not for profit, or part of the state’s infrastructure.

In this formalised setting ‘organisational structures’ are the system used to define hierarchy within an organisation and how delivery is monitored. It will outline who does what and who reports to who.

This kind of structure will affect the organisation’s actions and staff activities, with policies and cultural elements shaped around this and vice versa.The structure also determines how information and decisions are taken across the company.

Some organisations will be centralised, meaning decisions and information will flow in a top down way, whilst decentralised structures might have distributed decision making powers, sometimes shared across staff.

Equally, our services are often influenced by more informal organising structures at work within our organisations. There are often organising structures that are unknown to an organisation, undocumented or not officially defined, formed of informal networks or sub-groups set up on their own merit to help achieve the end goal.

In all cases, there is an element of organising people, assets and resources to work collectively towards a shared outcome and all have an equal impact on the eventual decisions that this organisation (whether formal or informal) makes about its services.

How do organisational structures affect the service?

Org structures can become visible to users, with services designed around siloed teams meaning users have to learn specialist language and mental maps to meet their user needs

When services are run by multiple different departments without clear ownership for service decisions or approval processes are complex, this can affect a services ability to respond quickly to feedback or emergent needs

Decisions around services can be taken by people multiple times removed from the frontline delivery and informed by specialised reporting, meaning the true needs of users might not be communicated to help make well informed decisions on user needs

The organising of people around functions and not services means that decisions made about the full stack of what powers services may be made based on organisational need and not in reference to a wider user journey leading to unmet needs or difficult to use services

Services can often be delivered by a team that then disbands once the service is live’. but without accountability for the continuous improvement of the service, this can lead to services failing over time from system updates to not meeting user needs

Improving the user experience can often fall between the cracks of different teams and their budgets. Even if a specific team wants to proceed in reviewing a service performance or improving it, politics, budget, resources might get in the way of doing so

Questions we can ask as leadership

- Does the way we’re structured help us make decisions that put user needs first?

- How can we organise ourselves to focus on the services we run?

- Are we enabling cross organisation decisions to be made?

- Do we have the right sign off / control in place to manage risks and empower frontline staff and teams responsible for services to improve and innovate services

- Is the structure and design of our organisation fit for the services we need to deliver now, and in the future?

- Who is really accountable for the end user experience of our staff and users?

Questions we can can ask if we work with this specific component

- What are the key strategic projects we need to run to align our organisation around the user experience?

- If we re-organise our organisations for more efficient or joined up delivery, do we need to consider job losses or role transitions?

- How do we organise ourselves to ensure we have accountability for the user experience and our services?

Information we need to understand before we start designing

- How are services managed and by who in the organisation?

- What teams have a role in delivering the service and is it set up to meet needs across the whole user journey?

- Are there any dead ends or delays in the service due to the organisational structure?

- What is the best way for an organisation’s tasks and activities to be portioned up to deliver this user experience?

- Do all our services have clear service ownership and activities based around continuous service improvement?

In order to deliver a service we need to be clear about who is responsible for what tasks and at what point in a service they are being delivered. The skills we have within our organisations, and the way we define those skills into specific ‘roles’ plays a huge part in our ability to organise ourselves to deliver our services.

In the context of services, roles can be assumed to look after specific parts of a user experience and carry out the tasks that need to be fulfilled as part of this. The proximity of roles to the service users can differ, with some working closely with users, whilst some roles work behind the scenes to power the service, never directly interacting with them.

In most organisations roles usually become more tightly defined as they get closer to a user, for example in a call centre. This level of definition can determine the amount of autonomy that staff can have to meet user needs and can sometimes constrict their ability to deliver the service a user needs

Equally, roles are sometimes so closely tied to the operation of systems and infrastructure that change to the role or system become intrinsically linked with one another, making both much harder to iterate and improve.

Overall, services need to be owned. There is a role for making decisions and prioritising needs that a service must meet and ensuring this is regularly reviewed. It is essential, even if the service is delivered by multiple teams and departments that there is a clear empowered role owning the end-to-end service who has the authority to make changes.

How do skills and roles affect the service?

Staff with inadequate skills to deliver an element of a service may delay processes in the user experience

Unskilled or inexperienced staff can put users at risk in a service

A lack of perceived or actual autonomy for staff in their roles can lead to a limit in the ability to meet user needs

The future delivery of a service may be at risk if the skilled workforce is not available

Some systems and infrastructure require such specific skills to operate that over time, both the system and role can become very difficult to change

When services go wrong it can take time to resolve issues if there is not a clear owner for the service to prioritise fixing it

Questions we can ask as leadership

- What skills does our organisation need to deliver services that meet user needs?

- What are our key regulatory or legal responsibilities we must ensure are covered by our roles?

- What skills does our organisation need to meet new or emergent needs in the future?

- Will our capabilities and roles need to change over time?

- Who is responsible when our services fail?

- How and when are roles and responsibilities measured against the user experience?

Questions we can can ask if we work with this specific component

- Do we have an audit process to gain an understanding of what skills our workforce have?

- Do we have a clear understanding of the skills and responsibilities needed to run our services effectively?

- Is there an accredited skill level needed to deliver the user experience and does this differ across different areas of delivery?

- What skills are we lacking to deliver the current service?

- Do we have the appropriate financial model in place to afford the right skills to deliver the service in the short to medium and long term?

- Do people have the right responsibilities enabling them to deliver the service?

- Are roles flexible enough with autonomy to deliver the service?

- Are roles and responsibilities clear for staff and users to deliver and use the service?

- Can responsibilities be flexibly shared?

Information we need to understand before we start designing

- What are the skills and roles needed in order to deliver the service and help users meet their needs / intended service outcomes?

- What responsibilities are fixed to a certain role or skillset to run the service we are designing, what are flexible and what are regulatory needs?

- Do we have a role responsible for owning the service now and in the future?

- What responsibilities and roles do and can users assume?

- Do we need more or less roles to deliver the service?

- Are there gaps in the service provision or user experience that need to be aligned to a responsibility?

- Are there any unwritten rules or negative power structures that stop staff from delivering the service?

- Have we designed roles and responsibilities for service failure?

- Can responsibilities be democratised across staff and/or users?

- What barriers stop or inhibit people on delivering in their roles?

Measuring performance is a key part of ensuring an organisation is meeting its overall goals. Measuring the outcomes of our services help us understand if we are delivering the impact we set out to deliver, but it also motivates us to do certain things in our organisations too. What we outline as a good outcome for services has an impact on how we design, deliver and monitor our services, and then incentivise this performance.

Most of the targets that an organisation has to meet are based on what the organisation, or whoever governs and funds it, deems to be important and believes will help them to meet their overall end goal. Our measurement frameworks and outcomes can be set by an organisation, defining what they think good looks like for users. Sometimes, this is set out in their policies or articles of association, or explicit targets related to their business model, profitability or Government priorities.

These might be a requirement to do something like improve health, reduce crime or social exclusion in return for credibility and funding to deliver their service. Whatever that target is, it will have a huge impact on the incentivisation of an organisation to deliver something.

Outside of the public sector there are an equal number or standardised ways we can measure performance – from Net Promoter Score (NPS) to Customer Satisfaction Score (CSAT) in much the same way as many of the public sector targets, these frameworks can help us to set what ‘good’ looks like for our services and measure them across different sectors.

It’s important to recognise though, that what an organisation thinks as ‘good’ outcomes for them is not always what is right or ‘good’ for users.

What we choose to measure in service delivery is important because it outlines what we believe good to look like. When done well, our approach to measurement can support an organisation to improve what it does on a daily basis and continue to improve in meeting user needs. When done poorly, it diverts attention from meeting end user needs.

Measurement, outcomes and the incentivisation of them must be treated very carefully. The implementation of any measurement system from targets to service-level agreements, balance sheet reporting to national performance frameworks can sometimes detract focus from whether or not services are actually delivering the things they need to do for our users. Reporting and the governance of performance data can sometimes become such an overwhelming focus of an organisation’s process that they forget to step back and ask – are we collecting the right data for the right thing in the first place. Is this really helping us improve what we do?

The implementation of performance measurement can operate at a variety of different levels from service level agreements (SLAs) between partners to individual staff targets that might be tied to a bonus scheme. All of these will have an effect on the way the organisation behaves and are vital to align to the organisation’s purpose,and what good looks like for our users.

Overall, the real test of good measurement is if it;

- is designed around solid evidence on what good means for users

- helps an organisation improve its offer iteratively

- is based on collecting and reviewing the right data

- Incentives in place don’t create divisions in overall delivery

How does measurement and incentives affect the user experience?

How we design and deliver services, and review their performance can be driven by measurements and incentives

Measurement indicators can sometimes be used negatively to show good performance but miss people most in need

What we define as ‘good’ creates a measurement system which in turn, dictates how we design services

Measurement and incentives affect the user experience by driving our attention to who we should and could help, and how

At a delivery level, measurements and incentives drive behaviour of staff who deliver the user experience

Incentivising individuals or teams to focus on performance can sometimes result in attention away from the user experience

Measurement frameworks can focus us on optimising one part of a service without considering the end to end experience

Questions we can ask as leadership

- How do we measure what good outcomes look like for our organisation?

- Do we have evidence to show what good outcomes are for users?

- What data does our organisation need to collect to understand if we are meeting the right outcomes?

- Is there any data we can stop collecting that doesn’t help us measure performance?

- Do the external reporting requirements we have help us meet user needs, and if not, can we influence them?

- Do we need incentives to improve delivery performance?

Questions we can can ask if we work with this specific component

- Did our incentive plans improve performance?

- Who are the right people needed in our organisational governance to review performance?

- Is the way we report performance helpful to reviewers?

- How are we performing in relation to others in our sector or wider system?

Information we need to understand before we start designing

- Have we talked to users about what good outcomes look like for them?

- What are good outcomes for our users?

- What evidence base do we have to understand what good outcomes are for users?

- Do we have evidence or research on what interventions are proven to work for the outcomes we’re seeking to design for?

- Who governs that outcomes are being met?

- Can our data collection processes to measure performance be improved?

- Do we understand what we can and should measure in relation to outcomes?

Who gets to make decisions, and how those decisions are made, shapes our services and the fabric of the organisations that deliver them. It’s therefore hugely important that we know how to influence those decisions as we work to convince people of your vision for what needs to change.

Authority should be treated as a material when a team starts work together and they should strive to find out how it works in relation to what they might need to change.This will help understand how they might be able to influence decision making at the right moment with the right material.

We should be questioning when decisions are made, who really makes them, and what influences those to really consider user needs as well as what decisions have been taken to inform where they entered the programme or project.

Working out who has the ability to make the decisions we need to be made is often not as simple as it seems though.

The ability to make decisions can be explicit in someone’s role within an organisation; where we can recognise that a person has the authority to make certain types of decisions because of their position in our organisational structure.

However, this official ‘authority’ doesn’t automatically give someone the power to action the decisions they make. While someone might have official ‘authority’ for decision making, they might have no available budget to deliver the decision they’ve made, no direct reports or even a low level credibility among more senior peers that impacts their power to make change happen. Likewise someone might have very little official authority within an organisation but be so highly regarded by peers that in reality they wield much more power in decision making than we might assume just by looking at their official role.

This happens because our organisations are social networks, made of real human beings, not just boxes on an org chart. Just like any other social network, some of the people that contribute to our organisations have more influence than others.

Understanding these two forces of authority (the decisions someone is supposed to be able to make) and power (the decisions a person is actually able to make) within our organisations is an important part of negotiating change to happen within a service.

In most typical structures, authority can usually be described as flowing from the top of an organisation to the bottom as part of a hierarchical structure.

In order to get things delivered, particularly at a complex scale of delivery, authority must be distributed evenly throughout your organisation to enable decisions to be taken at the right level. Giving authority away doesn’t mean resolving leaders of their responsibility but empowering those with the most knowledge to make the decisions they need to . Authority can be given by clearly stating what decisions others can take on an individual’s behalf, granting permission and designing in an accountability loop to check in on progress.

Importantly, without making authority levels clear within your organisation, unofficial power can easily take over as the primary means of influencing decisions, making decision making undemocratic and often exclusionary to more diverse groups. Power isn’t always fair and can be more centralised through cliques and close relationships or homogenised group think approaches.

Authority, and the dynamics of power is present in all forms of service design from how we approach designing services, to how services are delivered. Levels of authority can affect staff delivering services for an organisation. where staff feel governed by unwritten rules or by power structures that don’t actually exist, leading to a feeling of a lack of autonomy.

Authority and power also permeate the relationship between service provider and person using a service. For example, there is usually a power dynamic between doctor and a patient. Both have relevant experience and knowledge about an illness in question that can be considered as equal, yet we usually believe there is one set of expertise that is more important than the other. Power structures can easily become unconsciously designed by inherent biases or beliefs, that in turn affect our services. We must always question ourselves and the power dynamics at play when designing services.

Authority and power are inherent in the services we design and we must consciously talk about and design with it in mind or risk these things having an unconscious effect instead.

How does authority affect the service?

Authority has the power to stop investment in our services. If the right case isn’t created that ladders up to business and/or user outcomes then work will not start

The best case can be made for investing in a service to improve it but the actual authority is held by a decision maker who doesn’t value what users need. If authority isn’t clear within an organisation or properly distributed then unofficial power can overtake official authority and decision making becomes an activity for a privileged few, meaning ideas for improving services can be instigated without evidence or those with evidence don’t get taken seriously unless the ideas being put forward are by someone with power

Questions we can ask as leadership

- Do we have clear delegated authority in place to enable decisions?

- What are our key signoff processes for investment and approvals?

- Are our power structures clear to the organisation so they understand how and when they can make a case for change to happen?

- What is the balance between power and authority in our organisation and do we have an absence of clear authority meaning unofficial power is more important?

Questions we can can ask if we work with this specific component

- Is there a clear delegated authority across the organisation that people can understand?

- Are we clear on who has responsibility in our team to make decisions?

Information we need to understand before we start designing

- What power structures exist within our team?

- What do we need to do to influence the direction of this programme/project/service?

- Who needs to be influenced?

- What will really influence decision makers to focus on users?

- What power structures and dynamics exist in the system we are designing?

- Are we designing dominant models of power into our design – can we challenge it?

- Who has power in the situation we are designing and is this a good or bad thing?

- Who are the decision makers in relation to the services we are trying to design?

- Who’s not ‘in the room’ that has the real authority to make the decision

- What’s the chain of authority in the organisation or system to get sign off on our asks?

- Where and when do decision makers with authority to sign off asks meet?

The intent of an organisation is the thing that it wants to achieve. This could be to ‘reduce road deaths’, ‘be the best beverage company in the South West’ or ‘make it easy for people to get the groceries they need conveniently for less money’.

Whatever this thing is, it is often more detailed than just simply ‘making money’ (if a commercial service) or ‘looking after or supporting people’ (if a public service).

An organisation’s intent is the thing that defines what services it provides and why it operates.

This intent is often documented in a ‘mission’ or ‘purpose’, and, if that intent is fully supported within that organization, will be encoded in every layer that this organisation uses to think – from its policies and business models right down to it’s values and ethics.

When we’re changing a service it’s important that we consider each of these ‘thinking layers’ and the effect they will have on how that organisation behaves and what it does.

How organisations finance and sustain their services is largely driven by the underlying business model an organisation uses. A business model outlines the value to be delivered to service users and what value the organisation who provides it might gain in return. It covers who the intended users are, where revenue comes from and how this is invested, the products and services it might produce, how it might deliver those and what it needs in place to resource those things.

There are lots of different ways you can charge for your service, and define who will pay for this. Business to Business (B2B), Business to Consumer (B2C) subscription, rental, freemium and leasing are all examples of business models that are successfully delivered in today’s market.

A successful business model doesn’t need to consider money alone as the value an organisation will get from providing a service. This can be switched for a non financial resource like volunteering time or swapping something.

Business models can evolve at any stage of a service’s lifespan. Sometimes they are considered before an organisation is created to drive forward the creation of a new entity, in other cases, they evolve as an organisation is delivering services, adapting as they respond in real time to how people use their service(s) and markets change.

They can focus on delivering one service, or expand to cover multiple products and services over time, equally, new technology or channels can often be deployed to transform how a service is delivered in line with the model.